LTCM crisis |

||

|

The analysis of the LTCM crisis in this page has been proposed by Matthieu Benavoli (Ace Finance Conseil). |

LTCM was the famous acronym of “Long Term Capital Management”, a hedge fund, created and managed by John Meriwether. The mismanagement of the fund led to a major financial crisis in the 2000’s which weakened all the financial system.

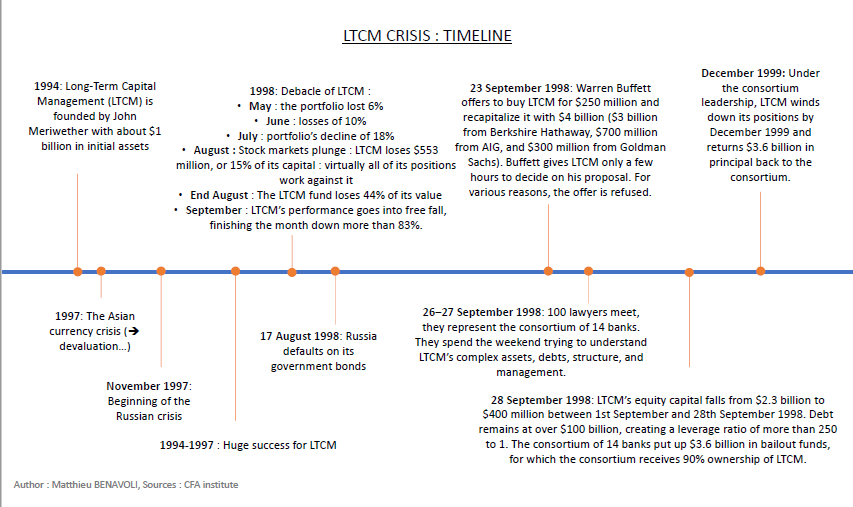

LTCM crisis timeline

Context

In the early 90s, the international financial ecosystem stood stable. However, one of the major financial event of that decade was the Reverse Plaza Accord in 1995. The United States enters this agreement to raise the value of the US dollar and force down the yen. The “Asian Flu” currency crisis begins with the devaluation of the Thai baht in July 1997. In the ensuing months, the crisis quickly spreads to other countries with similar financial profiles and currency pegs to the US dollar.

Birth

In 1993, John Meriwether, the famed Salomon Brothers bond trader, decided to craft a hedge fund. He got in touch with Merrill Lynch to rise funds and then created LTCM. Meriwether, holder of a MBA of the Chicago University, had a simple strategy: being accompanied by the most brilliant minds that could make his fund succeed. That’s why he assembled an all-star team of traders and academics in order to gather various academics’ knowledges (quantitative models…) and traders’ skills (market judgement, execution capabilities) such as Lawrence Hilibrandt (holder of a diploma of the MIT and extruder at Salomon), Eric Rosenfeld (former professor at Harvard), Victor Haghani (holder of a diploma of the London School of Economic), William Krasker and Gregory Hawkins (Phd in Economics at the MIT), David Mullins (vice-chairman of the FED) and Robert Merton (professor at Harvard) and Myron Scholes (professor at Stanford), recipients of the Nobel Prize in Economics. This team convinced sophisticated investors, including many large investment banks, to flock to the fund and to invest more than $1.3 billion. Among them we found Bear Sterns President James Cayne and his deputy, Merrill Lynch CEO, David Komansky, he Union Bank of Switzerland, the Chase Manhattan Bank and the Bank of China for example. However, the conditions to become an investor in LTCM were quite harsh: each of them should invest at least $10 million, which were blocked during 3 years, without any possibility for the investor to have a look at the transactions and with the highest commissions at that time.

Strategy

LTCM’s main strategy was to make convergence trades. Convergence trades involve two assets whose prices must converge with time and, at maturity (if there is a maturity), must be equal. Trades typical of early LTCM were, for example, to buy theoretically under-priced off-the-run US treasury bonds (it means bonds that were issued before the most recently issued bond of a particular maturity), they are less liquid and so less appealing for investors so a bit cheaper, and go short on-the-run, more liquid so with higher demand, treasuries. These trades involved finding securities that were mispriced relative to one another, then taking long positions in the cheap ones and short positions in the rich ones then due to the “convergence” effect, their prices should converge and in that case LTCM makes a profit. There were four main types of trade: convergence between on-the-run and off-the-run U.S. government bonds and long positions in emerging markets sovereigns, convergence among U.S., Japan, and European sovereign bonds, convergence among European sovereign bonds, hedged back to dollars.

LTCM realised some relative value trades too. Relative-value trades are speculative transactions based on belief that spreads will return to their historical averages. In principle, relative-value trades can be transacted between any two assets that have shown a strong historic correlation and whose yield spreads are outside the normal range. For example, LTCM took positions on the spread between U.S. government bonds and U.S. corporate bonds, between triple-A-rated corporate bonds and junk bonds, between U.S. government bonds and emerging market bonds, as well as on the difference between yields on the government debts of different foreign nations (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, China, Korea, Mexico, Poland, Taiwan, Russia, and Venezuela). Relative-value trades tend to have lower risks than outright (naked) positions because asset prices tend to change more than the spread between asset prices, but LTCM amplified these otherwise-diminutive risks by leveraging them with borrowed funds.

The success

Because of these positions, the fund needed the larger leverage effect as possible in order to make a significant profit. At the beginning of 1998, the fund had equity of $5 billion and had borrowed over $125 billion — a leverage factor of roughly thirty to one. LTCM’s partners believed, on the basis of their complex computer models, that the long and short positions were highly correlated and so the net risk was small.

In the first years this strategy scored a huge success: LTCM marketed itself as providing superior returns for risk that was no greater than that found in the US equity market. In 1994, LTCM gained 20% while the S&P 500 was up only 1.3%. In 1995, LTCM gained 42.8% while the S&P 500 was up 37.2%. In 1996, LTCM gained 40.8% while the S&P 500 was up 22.6%. In 1997, after two years of returns running close to 40%, the fund has some $7 billion under management and is achieving “only” a 27% return — comparable with the return on US equities that year. In 1998, the portfolio under LTCM’s control amounts to $100 billion, while net asset value stands at some $4 billion; its swaps position is valued at some $1.25 trillion notional, equal to 5% of the entire global market. It had become a major supplier of index volatility to investment banks, was active in mortgage-backed securities and was dabbling in emerging markets such as Russia.

The catastrophe

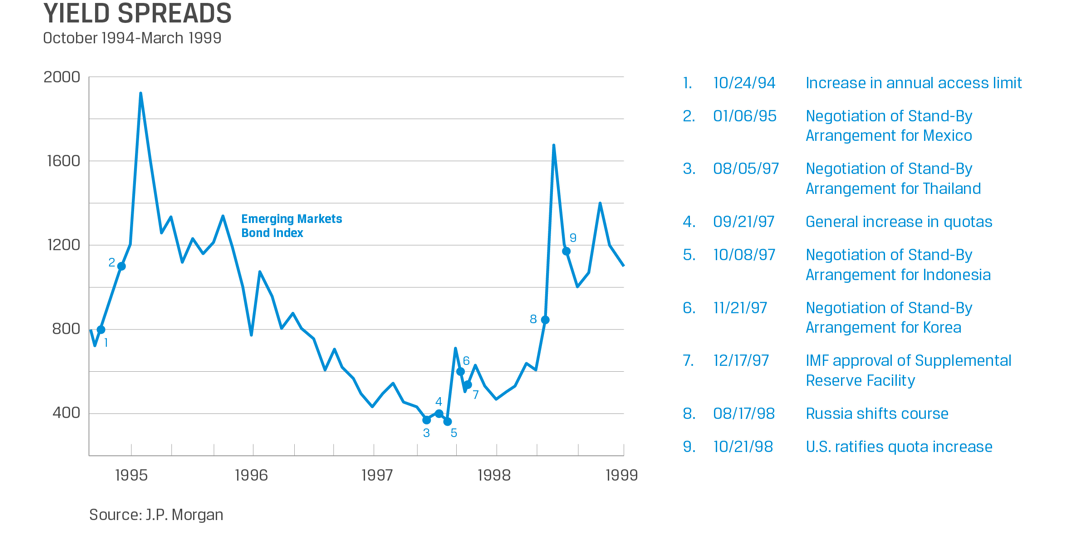

But the catastrophe occurred in 1998. In August 1998, Russia devalued the rouble and declared a moratorium on 281 billion roubles ($13.5 billion) of its Treasury debt. Russia’s default on its government obligations was one the aspects that explain the debacle of the fund. LTCM believed that its positions in Russian bonds were hedged by selling in the extent that a default on the bonds would undeniably lead to a collapse of the currency and so a profit could be made in the foreign exchange market that would outweigh the losses. Unfortunately, the banks on which the strategy of the rubble hedge relied on, collapsed too and the Russian government prevented further trading in its currency. This movement was so intense that LTCM’s equity dropped to $2.3 billion, but these losses were not significant enough yet to make the fund collapse. Under pressure, John Meriwether decided to permit potential investors to invest in the fund “on special terms” and forbade existing investors to withdraw more than 12% of their investment. The main cause of the LTCM crisis was what we could call “the flight to liquidity” across the global fixed income markets. As Russia’s troubles became deeper and deeper, fixed-income portfolio managers began to shift their assets to more liquid assets. While the U.S. Treasury market is relatively liquid in normal market conditions, this global flight to liquidity hit the on-the-run Treasuries (most recently issued securities) like a freight train. The spread between the yields on on-the-run Treasuries and off-the-run Treasuries widened dramatically: even though the off-the-run bonds were theoretically cheap relative to the on-the-run bonds, they got much cheaper still (on a relative basis). What LTCM had failed to account for is that a substantial portion of its balance sheet was exposed to a general change in the “price” of liquidity. If liquidity became more valuable (as it did following the crisis) its short positions would increase in price relative to its long positions. This was essentially a massive, unhedged exposure to a single risk factor. As an aside, this situation was made worse by the fact that the size of the new issuance of U.S. Treasury bonds has declined over the past several years. This has effectively reduced the liquidity of the Treasury market, making it more likely that a flight to liquidity could dislocate this market.

In September 1998, LTCM’s equity kept on melting down and dropped. Banks began to doubt of the fund’s ability to meet its margin calls but could not move to liquidate for fear that it will precipitate a crisis that will cause huge losses among the fund’s counterparties and potentially lead to a systemic crisis because all of the leveraged Treasury bond investors had similar positions and heavily linked with LTCM. Peter Fisher, executive vice president at the NY Fed, decided to take a look at the LTCM portfolio. On Sunday September 20, 1998, he and two Fed colleagues, assistant treasury secretary Gary Gensler, and bankers from Goldman and JP Morgan, visited LTCM’s offices at Greenwich, Connecticut. They were all surprised by what they saw. It was clear that, although LTCM’s major counterparties had closely monitored their bilateral positions, they had no inkling of LTCM’s total off balance sheet leverage. LTCM had done swap upon swap with 36 different counterparties. In many cases it had put on a new swap to reverse a position rather than unwind the first swap, which would have required a mark-to-market cash payment in one direction or the other. LTCM’s on balance sheet assets totalled around $125 billion, on a capital base of $4 billion, a leverage of about 30 times. But that leverage was increased tenfold by LTCM’s off balance sheet business whose notional principal ran to around $1 trillion. However, according to LTCM managers their stress tests had involved looking at the 12 biggest deals with each of their top 20 counterparties. That produced a worst-case loss of around $3 billion. But on that Sunday evening it seemed the mark-to-market loss, just on those 240-or-so deals, might reach approximately $5 billion (see graph) And that was ignoring all the other trades, some of them in highly speculative and illiquid instruments.

On the 21st, bankers from Merrill, Goldman and JP Morgan continued to review the problem. On the 21st, bankers from Merrill, Goldman and JP Morgan continued to review the problem. Goldman Sachs, AIG and Warren Buffett offer to buy out LTCM’s partners for $250 million, to inject $4 billion into the fund and run it as part of Goldman’s proprietary trading operation. The offer is not accepted. That afternoon, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, acting to prevent a potential systemic meltdown, organised a rescue package under which a consortium of leading investment and commercial banks, including LTCM’s major creditors, inject $3.5-billion into the fund and take over its management, in exchange for 90% of LTCM’s equity. Many banks took a substantial write-off as a result of losses on their investments. In the end 11 banks put in $300 million each, Société Générale $125 million, and Credit Agricole and Paribas $100 million each, reaching a total fresh equity of $3.625 billion It was the very first time that the Federal Reserve Bank of New York took the step of facilitating a bailout of a private hedge fund, out of fear that a forced liquidation might ravage world markets.

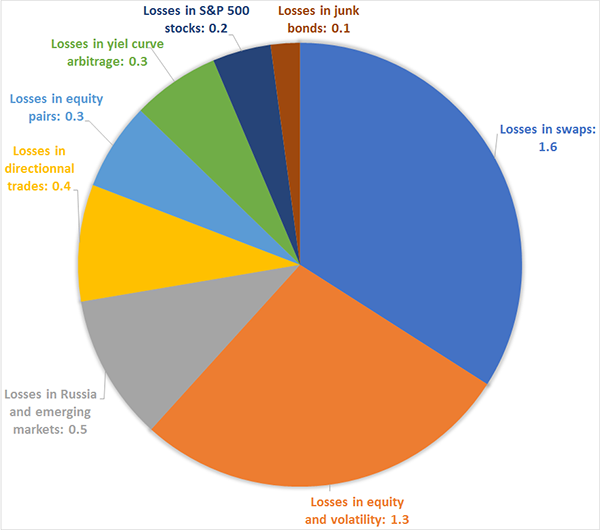

LTCM losses during the crisis

In the first two weeks after the bail-out, LTCM continued to lose value, particularly on its dollar/yen trades, according to press reports which put the loss at $200 million to $300 million. There were more attempts to sell the portfolio to a single buyer. According to press reports the new LTCM shareholders had further talks with Buffett, and with Saudi prince Alwaleed bin talal bin Abdelaziz. But there was no sale. By mid-December, 1998 the fund was reporting a profit of $400 million, net of fees to LTCM partners and staff.

Impact

Among the investors who lost their capital in LTCM (according to press reports) were:

- LTCM partners – $1.1 billion ($1.5 billion at the beginning of 1998, offset by their $400 million stake in the rescued fund)

- Liechtenstein Global Trust – $30 million

- Bank of Italy – $100 million

- Credit Suisse – $55 million

- UBS – $690 million

- Merrill Lynch (employees’ deferred payment) – $22 million

- Donald Marron, chairman, PaineWebber – $10 million

- Sandy Weill, co-ceo, Citigroup – $10 million

- McKinsey executives – $10 million

- Bear Stearns executives – $20 million

- Dresdner Bank – $145 million

- Sumitomo Bank – $100 million

- Prudential Life Corp – $5.43 million

There were no reported numbers for the following organisations: Bank Julius Baer (for clients), Republic National Bank, St Johns University endowment fund, University of Pittsburgh. As a side effect of this crisis, we could stress on the disappearance of the Ill fund

Lessons to be learned

- Market values matter: LTCM was perhaps the biggest disaster of its kind, but it was not the first. It had been preceded by Franklin Savings and Loan and the Granite funds. All of them three depended on exploiting deviations in market value from fair value and relied on shareholders and lenders who believed that what mattered was fair value and not market value. (managers convinced their stakeholders that because the fair values were hedged, it didn’t matter what happened to market values in the short run — they would converge to fair value over time. That was the reason for the “Long Term” part of LTCM’s name). The lesson learned from these case studies spoils some of the supposed “free lunch” features of taking liquidity risk. These plays can indeed generate excellent risk-adjusted returns, but only if held for a long time. Unfortunately, the only real source of capital that is patient enough to take fluctuations in market values, especially through crises, is equity capital.

- Liquidity risk is itself a factor: we should include liquidity in the stress testing by classifying securities as either liquid or illiquid. Liquid securities are assigned a positive exposure to the liquidity factor; illiquid securities are assigned a negative exposure to the liquidity factor. Using this approach, LTCM might have classified most of its long positions as illiquid and most of its short positions as liquid, thus having a notional exposure to the liquidity factor equal to twice its total balance sheet. liquidity must be anticipated. Not only must investors assess current liquidity conditions; they must also assess liquidity in the context of a realistic worst-case scenario (using past crises as guideposts).

- Models must be stress-tested and combined with judgement: even the most sophisticated financial models are subject to model risk and parameter risk, and should therefore be stress-tested and tempered with judgement.

- Financial institutions must aggregate exposures to common risk factors: many of the large dealer banks exposed to a Russian crisis across many different businesses only became aware of the commonality of these exposures after the LTCM crisis. A systematic risk management process should have discovered these common linkages ex ante and reported or reduced the risk concentration.

- On a more conceptual level, this case interrogates us about our real, deep comprehension of the mathematic tools we manipulate. For example, most of investors are convinced that volatility amounts to the risk: this is true from a mathematical point of view but the LTCM case unequivocally demonstrates that they are two different things: the volatility was measured and hedged but as the methods to reduce this volatility expand, the risk increased. In theory, for all the analysts, the risks taken by the fund was if not small, under control. This statement proved to be totally false. In the case of LTCM, the risk was measured by the “Value at Risk” method (VaR), which is a statistical technique to estimate the amount of losses a portfolio might incur over a given day or week (or longer) based on historical price movements: one of the main problem of this method is that it often creates a false sense of confidence that the investor has a handle on risk. Because VaR is focused on volatility of security prices, it is totally independent of fundamental sources of risk. In other words, VaR is neutral on whether an issuer’s debt levels are high or low, spreads are tightening or widening, currencies are pegged or free floating, oil prices are rising or declining, etc. Risk models, such as VaR, are theoretical in nature, while a portfolio’s actual risk of loss is based on circumstances and events that may not have been present in the historical data.

- One could argue that LTCM was just the victim of extreme market events and in another context, everything could have gone very well. Is this statement true? This theory implies that the Russian bond default came out of the blue… it is clearly false: the bond default, which is in itself an extreme event, was preceded by a series of unfolding events (for example the rise of the US dollar after the Reverse Plaza Accord which dampened Asia’s demand for oil and weakened the Russian economy as a side effect…), each of which escalated the risk of a default. Then the huge flight to safety and to liquidity which occurred after the Russian bond default was not really a surprise, this was a common phenomenon in times of crisis. As we explained the dramatic widening of yield spread (due to the flight to liquidity) after the Russian crisis was very harmful for LTCM, however, as we can see on the graph below, we cannot consider it as an exceptional event: a “higher pike” was registered just few years before: in 1995!

LTCM losses during the crisis

- So, investors have to keep in mind that sooner or later, markets will move against them for either good reasons or bad. Be prepared.

- It is a proof that deploying a highly leveraged position that does not allow for adverse movement in security prices is a recipe for disaster. For unlevered, diversified investors, mistakes are unfortunate, but they can live to fight another day. For levered investors, even small mistakes can easily become a crisis. And if the investment positions are large enough, the mistake may be a systemic risk, as in the case of LTCM.

A new financial risk: the pride risk?

Granted the LTCM is first and foremost a huge miscalculation story however one should keep in mind that this debacle is due to the pride of an all-star team which was composed by talented and skilled intellectuals who could not imagine they were wrong. Actually, as Warren Buffet underlined that “if you take John Meriwether, Eric Rosenfeld, Larry Hilibrand, Greg Hawkins, Victor Haghani, and the Nobel prize winner Myron Scholes and the rest of the LTCM team, these 16 people, they probably have the highest average IQ of any 16 people working together in one business in the country, including Microsoft or whoever you want to name–so incredible is the amount of intellect in that room. Moreover, they had, in aggregate, probably 350 or 400 years of experience doing exactly what they were doing and they had their own money tied up, hundreds of hundreds of millions of dollars of their own money tied up” so they were concerned about the gains and the losses of the fund, they put their own fortune at risk. He added “and they went broke. And that to me is absolutely fascinating. If I write a book, it’s going to be called “Why do smart people do dumb things?”. However, never before had a hedge fund, or any financial institution benefitted from such an impeccable reputation… Before the crisis. We could see this “ego risk” in the very last weeks of existence of the fund: LTCM’s top managers placed their vast personal wealth in the company, levered it up dramatically, and through their own hubris lost it all. As Warren Buffett said about the LTCM founders, “To make money they didn’t have and didn’t need, they risked what they did have and did need. And that’s foolish. If you risk something that is important to you for something that is unimportant to you, it just does not make any sense” (Housel 2012). Considering that these people were already so accomplished and so wealthy, it appears that they were motivated not by money, but by pride

“The big difference between those who are successful and those who are not is that successful people learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of others.”

— Sir John Templeton, CFA

References

LTCM Crisis – Case Study http://www.bauer.uh.edu/rsusmel/7386/ltcm-2.htm

Long Term capital Management – www.Investopedia.com

http://www.investmentreview.com/print-archives/winter-1999/the-story-of-long-term-capital-management-752/

Case Study: Collapse of Long-Term Capital Management – http://financetrain.com/case-study-collapse-of-long-term-capital-management/

JP Morgan

CFA institute: Case Study, Long Term Capital Management https://www.econcrises.org/2016/04/18/long-term-capital-management/

Warren Buffet, commencement address for MBA students at the University of Florida

Amadeo, Kimberly. 2014. “What Was the Long-Term Capital Management Hedge Fund and the LTCM Crisis?” About.com (8 October).

Chiodo, Abbigail, and Michael Owyang. 2002. “A Case Study of a Currency Crisis: The Russian Default of 1998.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (November/December).

Damodaran, Aswath. “Annual Returns on Stock, T.Bonds and T.Bills: 1928 – Current.”

Dowd, Kevin, John Cotter, Chris Humphrey, and Margaret Woods. 2008. “How Unlucky Is 25-Sigma?” Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 34, no. 4 (Summer): 76–80.

Fleming, Michael; and Liu, Weiling. Federal Reserve History. 1998. “Near Failure of Long-Term Capital Management.” Federal Reserve Bank, September 1998.

Housel, Morgan. 2012. “A Brief Reminder of How Fast Things Change.” Motley Fool (31 January).